Early History

Thomas Oliver was born in Woodstock, Ontario, Canada on August 1, 1852. In his youth, Oliver lived on his father’s farm, where he would tinker and build various devices such as windmills and threshing machines with only basic farm tools. In 1874, Thomas Oliver married Mary Ann Eddy in Paris, Ontario, Canada. Oliver relocated with his wife and children to Lansing, Iowa, where he became a Methodist Circuit Rider for the Upper Iowa Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church and began preaching.

Thomas Oliver

Thomas Oliver with wife Mary Ann Eddy

Reverend Oliver frequently traveled Iowa to various cities in his circuit to preach. In 1888, during his preaching travels, Reverend Oliver was sitting at a bank in DeWitt. It was there he saw a stenographer using a typewriter and observed its inefficiency, since the typist could not see what was being typed. He did not examine the machine because its mechanics appeared crude and upside-down. Oliver set out to create a better machine with visible writing so that his sermons could be typewritten.

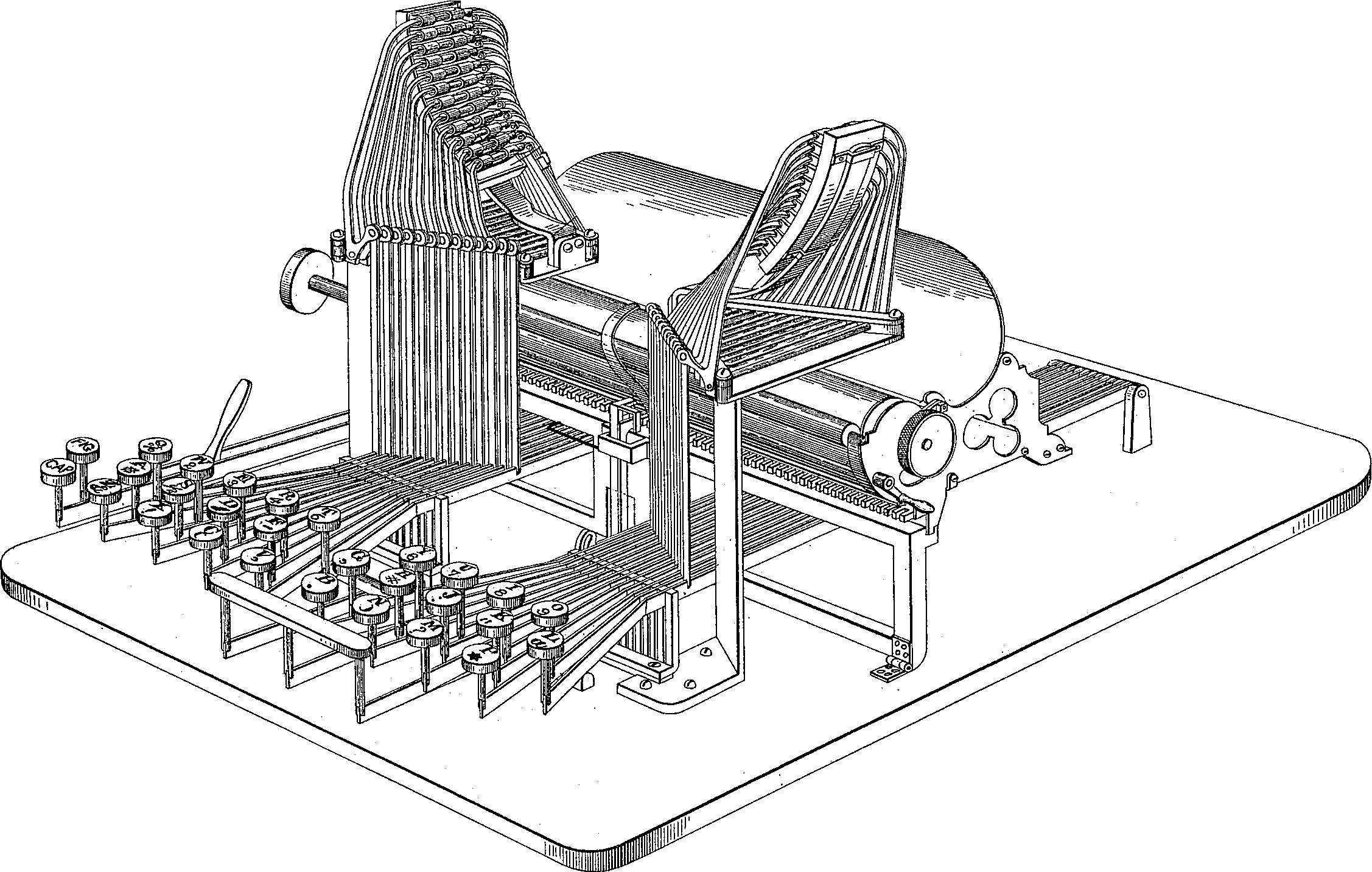

Oliver began prototyping that same year using crude and simple materials, including wire devices, strips of tin cans, and rubber. The typebars were arranged in a pivoting arc with a hammer mounted to strike them against the platen. This early design also featured an ink roller instead of ribbon spools. On August 26, 1890, Oliver filed his first typewriter patent, which featured the pivoting typebar arc design.

Reverend Thomas Oliver’s pivoting arc typebar design

In 1891, Oliver developed his second prototype alongside two machinists. The pivoting arc typebar design of this prototype proved unsuccessful, so Oliver continued to search for a better alternative. He eventually came up with the famous downstrike typebar design while he was in his study reading a book on machinery. He fell asleep in his chair and awoke shortly after, jumping and shouting “eureka” to his wife as he began to sketch a U-shaped typebar he saw in his dreams. He went to Dubuque to get old watch and clock springs to make the typebars for a prototype model. Thomas Oliver spent months perfecting this new downstrike mechanism.

On September 12, 1892, Oliver filed his second typewriter patent (now featuring the famous downstrike typebars). Once Oliver was satisfied with the downstrike prototype, he took it to Dubuque to put it on exhibition in the Noyes art store. Large crowds gathered, as the value of the machine was exemplified. Oliver eventually raised enough capital to organize a stock company.

Reverend Thomas Oliver’s U-shaped typebar design on a rectangular base

By this time, Oliver was residing in Epworth, Iowa where he had been developing the typewriter. The upstairs of his residence was utilized as a makeshift factory, where five machinists were employed. With the combined efforts of Thomas Oliver and these employees, twelve typewriters were produced over the course of a year. The bases of the machines were cast by the Adams foundry while other parts were furnished by more local industries.

Reverend Thomas Oliver’s Epworth residence

Oliver No. 1 illustration in U.S. Patent No. 542,275

On September 19, 1893, Oliver filed another typewriter patent featuring the downstrike typebars. The machine of this patent possesses the final shape of the Oliver No. 1 base and includes ribbon spools.

The first factory of the Oliver typewriter

To increase production, an application was submitted by Oliver to city council for assistance. In response, a two-story brick factory was constructed in 1894, just north of the Illinois Central railroad tracks in Epworth. This new factory employed 16 workers once it was completed. They were now able to produce six machines per week.

Oliver No. 1 illustration

Naturally, Oliver wanted to continue scaling the company to increase production. On September 18, 1895, Thomas Oliver and capitalist Douglas Smith went to a meeting of the Racine Business Men’s association in Racine, Wisconsin to try and secure funding for a larger manufacturing plant. They presented the Oliver typewriter and all of its advantages to everyone in attendance and the feedback was very positive. Oliver and Smith wanted to relocate to Wisconsin because of the availability of skilled machinists.

On October 15, 1895, the committee met again to discuss forming a company there to manufacture the Oliver machines. Two days later at the next meeting, the committee reported that they are in favor of a typewriter factory in Racine. They believe the machine was superior to all other typewriters on the market at the time and congratulated Thomas Oliver on his invention. The committee’s report proposed the people of Racine subscribe and pay for capital stock of the company to be organized. Thomas Oliver and other stockholders would have to turn over the patents and good will for the new company’s capital stock. Twenty percent of this stock was to be spent as needed by the company. Thomas Oliver would receive a royalty on each machine manufactured and sold.

By December 6, 1895, the Wisconsin capitalists formed a plan rebuild the Scotford plant in Kenosha, Wisconsin (south of Racine) to use as the Oliver factory. The Scotford plant was two stories tall, 12,000 square feet, and would be equipped with a 50-horsepower boiler and engine. Fifty skilled machinists would have been initially employed, with operations to begin the following spring. Zalmon Gilbert Simmons, Sr., founder of the Northwestern Wire Mattress Company was funding sixty percent and thirty-seven percent was to be funded by the citizens of Kenosha. Only the remaining three percent stood in the way of securing the deal.

Tappan Steam Pump Company

Before officially closing on the Wisconsin deal, Oliver and machinist Charles Fay went to Woodstock, Illinois, to seek out one more potential relocation opportunity. Two years prior in 1893, to attract more industry to the area, an 80-by-200-foot brick factory was built with capital raised by Woodstock residents for the Tappan Steam Pump Company. However, this company only lasted two years. In order to fill the empty factory and bring another major business into the area, a deal was offered to The Oliver Typewriter Company by the Woodstock Public Improvement Association. If Oliver stayed in Woodstock for at least five years and employed 150 workers by that time, the factory would be donated to the company. Oliver readily accepted this offer, and the Kenosha relocation plan was forgotten.

On December 29, 1895, The Oliver Typewriter Company was incorporated as a new stock company. On January 14, The Oliver Typewriter Company took possession of the Woodstock factory, and on January 16, Oliver's machinery was shipped from Epworth to the Woodstock factory. The Woodstock factory first opened with 80 employees, 15 of which were from the Epworth factory. Production was initially slow, but significantly increased over the years to come. By 1901, over 200 employees operated the factory, often working into the evenings to keep up production.

Workers leaving the Oliver typewriter factory for lunch

Reverend Thomas Oliver's cotton harvesting invention

In addition to the eponymous typewriter, Oliver also invented other devices, including a cotton harvester. On Saturday, February 6, 1909, an improved cotton harvester prototype designed by Oliver was to be shipped from Chicago to Pine Bluff, Arkansas where it would be set up the following Monday. On Wednesday, February 10, Thomas Oliver would demonstrate his machine to government officials four miles east of Pine Bluff.

Reverend Thomas Oliver

Unfortunately, the fate of Thomas Oliver took a different course. On the afternoon of February 9, 1909, Oliver and his second wife, Danish immigrant Olga Ottonia Christiane Nielson, arrived at the Argyle train station, part of the Northwestern Elevated Railroad. They were on their way to Pine Bluff by way of the Illinois Central Railroad. However, the pair never managed to board the train. Thomas Oliver suddenly collapsed in his wife’s arms due to heart failure at 56 years of age.

The following Thursday afternoon, the Oliver Typewriter Company held a memorial in one of the largest rooms in the factory for the late inventor. The superintendent, his assistants, around 1,000 employees, and several hundred citizens of Woodstock attended the memorial. On February 14, 1909, Oliver’s body was delivered to Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.